Cheese insiders know Adam Moskowitz. Maybe they do business with Larkin or Columbia Cheese, as most cheese sellers do regularly. Maybe they’ve watched Moskowitz on stage at The Cheesemonger Invitational (CMI), rocking his cow costume and belting out cheese raps. Moskowitz and his businesses deeply impact most territories in the sprawling land of cheese.

Recently, Moskowitz took me on a tour of Larkin, his 40,000 square foot warehouse in Long Island City, Queens. Larkin has 27,000 square feet of cold storage — that day, there were eight truckloads of pickles alone. But mostly, the terrain is vast quantities of cheese, wheels and boxes marked for Pasadena, Denver, Boston and beyond. Many warehouses are caked in grime, but the floors at Larkin glisten. Outside, trucks spill onto the street.

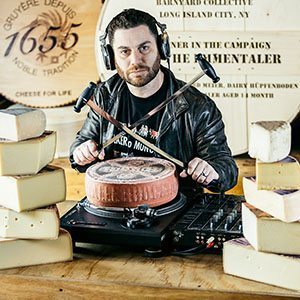

Larkin boasts a woodworking studio, where Moskowitz’s employees recycle pallets for creative fodder. The Adirondack chair that sits outside used to be a pallet full of cheese. In Moskowitz’s classroom, home of his latest project, the Barnyard Collective, he shows me his DJ equipment. He blasts some tunes and demonstrates the disco lights, which whir neon around the airy room. This is going to be fun. Things with him usually are.

Cheese Connoisseur: You wear a lot of hats in the cheese world. Can you walk us through what you actually do?

Adam Moskowitz: My heartbeat is Larkin Cold Storage. We’ve been in the building since 1978, and took ownership of the building in 1992. We are a Container Freight Station (CFS), which means we’re allowed to move containers from port to building and clear U.S. Customs and FDA on premise. So we can expedite goods fast.

Our sister company Euro Larkin in Rungis, France receives products from all over the EU on a weekly basis, then consolidates them into containers for shipment to Larkin here in America. We are the logistics partners for about 40 different importers of record. It’s simple — we go from France to New York, every week, 52 weeks a year. In 2015, we imported 7 million pounds of cheese.

We are a vendor-based warehouse, too. We store product, manage inventory, create orders… and for some companies we even manage billing and banking. Pretty much everyone in the cheese business — any major importer or distributor — comes to Larkin on a weekly basis.

I’m the third generation in this industry. My grandfather owned a company called Walker Butter and Egg. My father left Walker and started Larkin in 1978. And I bought my father out of Larkin and Columbia Cheese in 2013.

CC: It comes across really clearly that you love what you do.

AM: I’m 41 years old and still drive my forklift. I may be the highest paid forklift driver in America.

CC: Larkin is just one of your businesses. Can you tell us about the others?

AM: Columbia Cheese is an import company that sources, markets and sells exclusive product from Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark and Ireland.

With Columbia, my mission is to support traditional village dairies. By traditional, I mean the ethos, not the product. Challerhocker is a new school cheese. I love rockstar cheesemakers and I love best in class. My focus is the very best. 1655 is the very best Gruyere in the world. That’s a fact. That’s who I am.

I work on projects that are redefining. For example, we introduced Challerhocker to the U.S. We were the first to import Ciresa Taleggio, the best Taleggio available in America. We introduced Chiriboga Blue and Adelegger from Bavaria, and Mycella from Denmark.

I also love a tough project. Everyone’s afraid of Limburger. So we represent Anton’s Limburger which is creamy and buttery. Yes, there is a layer of funk, but it is balanced. We represent a traditional Havarti maker — it’s not the boring, plastic-tasting bullshit that we all know.

The Cheesemonger Invitational (CMI) started as a party in the warehouse. I had nine cheesemongers from some of the best cheese shops in the country compete. It was a competition and a party at the same time.

Now we are working on our tenth event. It’s turned into a whole weekend affair, with more than 30 mongers competing in each one. We have given away thousands of dollars in cash, tons of tools and many, many trips. Hopefully, we inspire. We try to help cheesemongers see the whole supply chain, the beauty of our industry. When you are selling cheese, you are supporting agriculture, farmers and artisan producers. You are supporting generations of cheese tradition, which is sexy and important.

CMI is my favorite part of the job. I want to change lives and inspire people. I love hospitality and hosting. I love having fun. As cheese people, we all live in our shops, our make rooms, our warehouses. We spend so much time independently. Here, the cheesemakers get the spotlight, everyone gets to meet and network.

The CMI is like pure foie gras, or even better true tyrosine. The finest bits of our industry, distilled. It really, really turns me on. We’re going on our tenth one, and I’m even more excited for the tenth one than I was for the for first one.

CC: Larkin and Columbia Cheese inspire people, too, just in a different way.

AM: Larkin’s a warehouse — I’m able to improve the lives of my staff. It’s home, which I love. My employees at Larkin are some of the unrecognized pillars of the industry. They have been with me for a long, long time. My warehouse manager Ernie has been here for 20 years. The forks of his forklift have lifted millions and millions of pounds. He has personally maneuvered so much of the cheese consumed in America. He is an unsung hero of cheese.

At Columbia, we support cheesemakers and agriculture. Like Walter Rass, who makes Challerhocker. We have directly and profoundly affected his family and his farmers’ families. We made his ceiling of opportunity unlimited. That’s revolutionary in such a beautiful way.

CC: You always have a new project brewing. What’s next?

AM: The CMI inspired my latest, the Barnyard Collective. I created a cheese education room in my warehouse. Over the last year, we’ve been bringing 50…60…70 cheese professionals together regularly. No outsiders. It’s private. We want to cater to and inspire the professionals.

For example, I’m really into discussing sensory profile over flavor profile. Flavor profile is just taste and aroma. But there are more senses to discuss — like sight, sounds. Crunch is important!

CC: You didn’t grow up loving cheese. How did cheese win your heart?

AM: My parents got divorced when I was two years-old, and I lived with my mother in New Jersey. I didn’t grow up in the business, although I’d see Larkin when I visited my father on the weekends.

My mother was a single mom with three jobs, she inspired my worth ethic. It was a tough road. I’ve been working ever since I can remember. I had a paper route; I was a babysitter. My first real job was at a place called the Penny Pantry where I stocked refrigerators with milk for most of the day. Then I worked as a busboy at the local diner. I was a Good Humor ice cream man…again, more dairy.

I went to college at George Washington University, where I started my own valet company. After college, I came to work for my family and realized this warehouse business is really, really difficult. I didn’t think I could handle it. It was too much. The idea of continuity was so important to my father. When I left, I disappointed him greatly.

But I went elsewhere — I wound up getting an Internet job, for a company called Yahoo. I got into sales and business development for Internet companies, made a million dollars by 23, and lost a million dollars by 25. It was emotionally taxing. Thank God that while all my other friends were buying Porsches and going to the Hamptons, I was buying records and going to the Poets Café.

At the age of 30, I decided to be a rapper. I sold the remainder of my Yahoo stock to produce an album (check it out at thebeatpoet.com).

When I was 32, my grandfather passed away. He was a pillar of the cheese industry, and of the Jewish community, and was an all-around awesome, inspiring individual. I had been floating, and thinking about moving to LA, but I stayed close to home to support my father.

The Yahoo money had run out. I had a great album, but I felt lost. I wasn’t getting amazing women to love me. I was kind of unstable and partied really hard. Even though I was creatively fulfilled, I was drifting. I had to pivot.

At the time, my father had decided to sell Larkin. That legacy was over for me. Still, I decided to honor my family name and learn more about cheese. I didn’t know much at all. Also, I needed some cash. I started working at a place called Formaggio Essex in the Essex Food Market in downtown Manhattan. It was a super tiny, 200 square-foot cheese shop. I fell in love with cheese. It was a revelation. It connected me to the land, to people, to my dad and my grandfather.

Being a cheesemonger was the best job I ever had. I had jobs with six-figure incomes and this was a $13/hour gig, and I never felt more fulfilled in my entire life. It transformed me not just into a cheesemonger, but into a cheese head. I left work with my pockets lined with cheese. I’d go to a bar and make friends with everyone, eating cheese and drinking with a bunch of strangers, talking cheese. I’d prepare Blue cheese tours of Europe for my dad, which blew his mind, because a few years before, I didn’t like Blue cheese.

I worked with Formaggio Essex for about six months. Lo and behold, the deal my father was trying to close fell through. He asked if I wanted to take over Larkin. It was such a big deal — it was not what I was planning. I was very serious about being an artist. I was deeply focused on making it in entertainment. I wanted to be an artist, and here’s a warehouse.

CC: What was returning to the family business like?

AM: I grew up with the idea that going into the family business meant you had failed in the real world, couldn’t make it elsewhere. But at the same time, I felt this enormous pressure to step into these big shoes, wear them, and get bigger shoes. After a tremendous amount of consideration, I decided to take advantage of the opportunity.

I also decided that finding an amazing woman and starting an amazing family was really important. I had new priorities for myself. Taking on my family business was a path to getting what I ultimately wanted, a path to family.

And eight years ago, I took over Larkin, a year after that we launched Euro Larkin, then Columbia Cheese and then the CMI. And I’m very proud to say that the gross revenue of our group is five times what it was eight years ago.

I was able to buy my father out of the business. It wasn’t given to me; I wouldn’t accept that. He spent his life investing in this company and I am able to help him get his money out. That’s what I’m most proud of, along with my own family — my beautiful wife, my beautiful son and my baby girl on the way.

CC: You’ve been incredibly successful. Why do you think that is?

AM: My childhood taught me to be very self-reliant, optimistic, to never give up. I’ve learned that nobody’s going to do for you what you want to, what you can do for yourself. You have to do for you.

I would not have traded my childhood for the world. I am a big believer in community. Why? I was a latchkey kid. I was an only child. So close friends coming together is important for me. My love of entertaining is driven by that.

CC: Did taking over Larkin make you closer with your dad?

AM: Growing up with divorced parents, there was a lot of animosity. But when I was performing in the city, my dad came out one night and told me how proud he was. I learned he was my biggest champion, and saw me in a light that I didn’t even see myself. He could be my mentor. I never had a mentor before.

When I took over Larkin, I acknowledged that I would have to shelve the poetry, art and music. It was a commitment; I could not fail. I had to show the industry that I was worthy of my name. To this day, I still meet people who speak of Ben and Joe Moskowitz as if they are legends, which they are. I took all of my creative energy and put it into the business. All of the care and commitment I had put into slam poetry, I put into driving my forklift. Everything comes full circle, because now I do things like the CMI. I’m on stage in front of a thousand people, which is where I wanted to be in the first place.

CC: You are the rock star of cheese.

AM: Thank you for that compliment. I’m just me. We all have gifts and passions. It’s not up to anyone else but yourself to explore them and honor them. If you do that, good things happen. Quality of life isn’t how much money you make — it’s how much you enjoy your life. How do you feel when you wake up, go to bed, go to work or eat? If you enjoy what you’re doing, you will enjoy success.

I feel really lucky and blessed. I love the cheese. I love the people in the cheese industry.

CC: People in the cheese industry are unusually wonderful.

AM: They are what drew me to it. Talking about cheese and pairing was so poetic to me. As an artist, cheese naturally fits.

My new mission — I always have to be on a mission — is to get more people comfortable with their palate. I want people to feel comfortable talking about food, flavor, and experience…with sensory profiles and lexicon. The more we are comfortable with language, the more our civilization will grow.

I am saddened by the food fear and intimidation that the general consumer feels. Cheese is at a pivotal moment, where wine was 20 years ago. It’s very important that we don’t complicate cheese, the way wine is often made complicated. Doing so is limiting, segregating and classist. Cheese is a peasant food: how families came together to share and pool their milk for sustenance. That’s the past, and I hope it’s our future. CC