For decades, the words “swiss cheese” were riddled with sapless connotations and visions of yellow apertured cheese with a bland texture.

The reputation was gleaned largely from large, format-style cheeses, including mass produced versions of Emmentaler, Gruyère and Raclette, which were exported at the expense of artisan varieties. But those days are over. Once ruled by the subsidies and production controls of the government-funded cheese cartels, the Swiss cheese market has experienced a renaissance, as cheesemakers have begun to reimagine the identity of this variety.

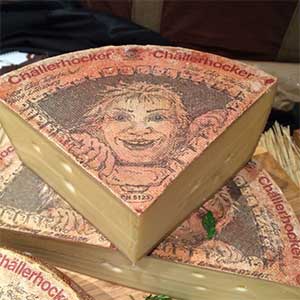

Among the game-changing Swiss cheeses that have appeared in the U.S. market in recent years is Chällerhocker, a traditional aged cow’s milk cheese from a small creamery in Lütisburg, Switzerland, near Zurich.

The name, pronounced “holler-hocker,” can be roughly translated as “sitting in the cellar.” And cellar-aging is one of the things, in fact, that differentiates the cheese from its regional cousin, Appenzeller. Unlike Appenzeller, which is often put on the market after just a few months, Chällerhocker spends at least 10 months on wooden planks, each wheel carefully turned and brushed with a simple salt water brine.

Chällerhocker is made by cheesemaker Walter Räss. Its milk is delivered twice daily from 13 family farms, each within about a mile’s radius of the dairy. The diverse flavor, which is directly influenced by the mix of flowers, herbs and grasses unique to the Alpine pastures on which the cows graze, offers up vegetal notes like sun-drenched hay and leeks, along with browned butter and a hint of caramel sweetness on the cheese’s finish.

“It has this consistent cauliflower note,” says Adam Moskowitz, owner of Columbia Cheese, located in Long Island City, NY, the cheese’s exclusive U.S. importer. “There are notes of macadamia and pecan, and then you have a little bit of cooked onion or leeks. It hits those vegetal notes that I don’t think people are expecting from that style of cheese.”

The Chällerhocker Story

Nestled in the small town of Lütisburg, Switzerland, Kaserei Tufertschwil is a village dairy that has industry roots going back to 1896. It was purchased by the Räss family in 1987, and Walter Räss Jr. assumed operations with his wife Annelies Räss-Huser in 1992.

For years, Kaserei Tufertschwil was known for its production of Appenzeller. In fact, between 1990 and 2013, Räss was named among the top 10 Appenzeller producers 16 times. But, in 2001, prompted by a request from his brother-in-law Urs Huser, Räss branched out into new territory, making a cheese that would fundamentally change the future of his small-town creamery.

“My wife’s brother was one of the first importers of Jersey cows in Switzerland,” says Räss. “This group of breeders was looking for producers to work with their product. Urs [Huser] asked me if I knew someone who could make cheese with a little quantity. After a time, I told him I could make cheese.”

The milk’s fat content was higher than that gleaned from the more traditional Brown Swiss cows used for Appenzeller production, but Räss says he wasn’t dissuaded. Instead, he took the full, unskimmed milk, added yogurt-based cultures made by Annelies along with house-made rennet, and pressed the resulting curd into 15-pound wheels, which were brined and placed in the cellar to age.

Räss says after three months, the cheese was “hard with little taste,” but after eight months “it was wonderful.” The flavor had increased and the texture of the cheese had softened. Chällerhocker had been birthed.

Determined to take the cheese to market, Räss says he approached two Swiss retailers. One declined to sell the cheese. But, Molkerei Fuchs agreed to take on regional distribution for the line, provided it had a name and distinctive label.

“Our architect was a painter, too,” notes Räss. “And he is creative. We asked him for a name and a label. After 48 hours, I got a list with 15 names and he told me that for every name he had a picture in his head.”

It turned out that Räss chose the last name on the list, “Chällerhocker,” and the label came to fruition, depicting a bizarrely whimsical boy peeking out from behind a wedge of bricks.

“It is a young man who works in the cellar or aging room,” says Räss. “He holds the stones from the wall and calls up: ‘The cheese is ready to eat.’”

Devouring Chällerhocker

Chällerhocker’s texture, which is immodestly silky and a bit like fresh fudge, makes it spectacular for eating out of hand. Smoother and less grainy than Gruyère and less waxy than Appenzeller, its flavor is deep and lingering, making it an ideal cheese for noshing during the winter months.

It has no need for overpowering accompaniments, though Chällerhocker is a lovely addition to cheese plates, where it dances well with sweets like figs or dates, and pickled items, including cornichons and plums. It also shines when served with caramelized onions.

Because it melts beautifully, it’s an indulgent addition to macaroni and cheese, rösti or cauliflower gratin. Chällerhocker also provides a delightful way to elevate a humble grilled cheese sandwich into something worth remembering.

Chällerhocker’s nutty notes are complemented by fortified wines like Port, Sherry or Madeira as well as darker beers, including nutty brown ales, Oktoberfests and Dopplebocks. However, a less traditional, but equally delicious, pairing is the classic old fashioned cocktail.

“The aromatics in the drink — from the bitters and the brandy or bourbon — match so well with classic Alpine cheeses,” notes cheese blogger Tenaya Darlington (a.k.a. Madame Fromage). “They underscore herbaceous notes and play off their caramel sweetness.” She suggests enjoying the pairing fireside for full effect.

A U.S. Blockbuster

It’s not uncommon for a Swiss creamery to manufacture a unique cheese. Most have at least one house variety, which is made and sold onsite to local villagers. Yet, Chällerhocker was destined to be something more.

By May of 2014, says Räss, 80 percent of his production was Chällerhocker and demand for the new cheese was growing. So, despite his history and success with Appenzeller, he made the decision to shift his production entirely to the new cheese.

“I was a proud and good Appenzeller producer,” he notes. “It was not easy to do this step. We made this choice because Chällerhocker was our ‘baby.’ It opened a new world to us… the cheese world.”

The doors were opened even further when Columbia Cheese, an importer known for efforts in pioneering worthy cheeses from small producers, introduced Chällerhocker to the U.S. market in 2006. The cheese took America by storm, and today the majority of Chällerhocker produced and exported from Kaserei Tufertschwil is sold by cheesemongers across the nation.

It’s a phenomenon that underscores a key tenet of Columbia Cheese’s mission and this is that globalization doesn’t need to revolve around commodity products. Rather, notes Moskowitz, it can “reward small businesses that observe best practices with an entrepreneurial spirit.”

“Walter took a great risk in trying to produce a better product and create his own brand,” says Moskowitz. “And for that, he had to manage and take responsibility for the product and the business. So many cheesemakers in Switzerland are happy with the way things are. They say ‘I’m a cheesemaker. This is what I do. This is my life. It’s a good life.’ But Walter wanted better. Watch the movie ‘Jiro Dreams of Sushi’ and imagine that Walter is Jiro, only younger. And every day he gets his cook on making cheese. And every day he just wants to be excellent.”

Celeriac And Potato Gratin With Chällerhocker

Serves 4-6

Ingredients:

Butter, for gratin dish

1 lb celeriac, peeled and sliced to a thickness of about 1/8 inch

1 lb Yukon Gold potatoes, sliced to a thickness of about 1/8 inch

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 Bay leaf

¾ cup cream

½ cup milk

Salt

Pepper

5 oz Chällerhocker, grated (about 2 cups)

Preheat oven to 375 degrees. Grease a 2-qt gratin dish with butter, and set aside.

Place the garlic, milk and cream in a saucepan over medium heat. Allow to cook until it reaches a slow simmer. Season with salt to taste, and remove the bay leaf.

Layer 1/3 of the vegetables into the prepared gratin dish, alternating potatoes and celeriac. Season with salt and pepper, drizzle with 1/3 of the cream and topping and 1/3 of the grated Chällerhocker. Repeat to create three layers.

Bake for 1 hour or until the gratin is bubbling and browned and vegetables are tender when pierced with a knife.