Unless you’re a professional rally racer, the crushed gravel road leading to Capriole Goat Cheeses forces you to drive at about 10 mph. The unusually harsh winter of 2014 pocked the soft road with holes, which are now brimming with grey water from recent rains. A dense stand of trees concealing Judy Schad’s award-winning cheese operation leaves one guessing around which corner it’ll appear.

“We thought it would be neat to get away from the city when we bought this place,” says Schad, who moved to Greenville, Ind., four decades ago. “What were we thinking, right? We’re so close to Louisville, KY., but you would think we lived in no-man’s-land.”

Schad simultaneously loves and loathes the 80-acre farm. Her historic home, one-third of which was a stagecoach stop in the early 1800s, is about 50 yards from the cheesemaking operation and a few goat barns. She and husband, Larry, love the ample peace and quiet afforded by the rural location, but they’re city folk who love Louisville’s booming restaurant scene.

“Restaurants are just fun, don’t you think?” says Schad. “Especially the chefs. They like what we’re doing. They understand it. And I like working with people who appreciate what we do.”

What Schad has done for nearly 40 years is make some of America’s best regarded goat cheeses, award-winning Chèvres she began toying with in 1976. Back then, only a handful of American cheesemakers made Chèvres, which Schad created with milk from her children’s 4-H show goats.

“The truth is I had no idea what I was doing, and the cheese was not great back then,” she says, walking through her diminutive production plant. The constant dripping of whey through cheesecloth makes it sound as though it’s raining inside, and as a pair of cheesemakers scoop curd from a 300-gallon vat, Schad shifts the story a little and points to their work.

“This is the good stuff, made the right way,” she adds. “And getting here takes a hell of a lot of time and practice.”

When Schad launched her cheese business, it was called Capriole Farmstead Cheeses, “because I wanted to prove — to myself and others — that it could be done, that you could produce your own milk from your own herd and then make cheese all in the same place. But I really didn’t have any choice because there was no goat milk supply back then. And there’s not much more now, in Indiana, at least.”

In 2012, at age 69, Schad sold her herd so she could concentrate solely on cheesemaking. Now a central Indiana family oversees the herd, whose feeding, breeding and milking she and a few farm hands previously managed.

She says she should have sold the herd “ages ago, because now the cheese is better than ever. So much better!”

It’s easy to detect a note of perfectionism in her tone.

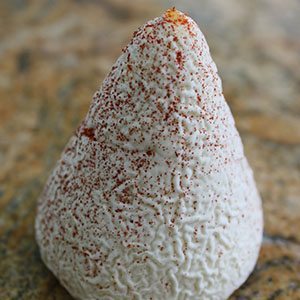

“From a cheesemaker’s perspective it is better for sure,” says Schad, now 71. “I notice things others don’t. I want that mold on that Wabash Cannonball to be wrinkled every time, and now it is. It’s taken a long time to get here, but I think we have arrived.”

Finding Her Whey

An excellent storyteller, Schad, a former high school and college English instructor, loves to laugh, especially at herself, when recalling Capriole’s clumsy start. In the early 1980s, she and cutting-edge Chèvre makers Mary Keehn of Cypress Grove Chèvre and Allison Hooper of Vermont Creamery, regularly talked each other through production problems, marketing ideas and struggles to stay afloat.

“At least I had the Bank of Larry to fall back on,” laughs Schad, referring to her attorney husband, who pitches in at Capriole when not working on malpractice suits. “Mary Keehn was a divorced mother of four who had to make this work. And when we all started, there was hardly anyone doing goat cheese. It wasn’t easy for anybody.”

Joining the American Cheese Society in the early 1980s humbled, educated and motivated her to improve her products.

“I was scared to let anybody taste them because I didn’t think they were any good,” says Schad. “They weren’t that bad, but I had a long way to go.”

That included developing Capriole into a workable business. Hardly anyone in Louisville or Indianapolis, which is an hour and a half away, knew anything about goat cheeses, so she set out for Chicago’s Green City Market, a five-hour drive north.

“That’s where it started to take off,” she recalls. “By then we were making some pretty good cheese, and people liked it. It’s inspiring when they tell you that.”

In 1987, demand pushed Capriole to construct a small, purpose-built production facility. The goat herd expanded, the milk flowed out and a modest amount of money flowed in. Predictably, the workload grew exponentially.

“You talk to cheesemakers and they all say, ‘I never thought it was going to be this hard!’” she says. “We all got into this business with the romantic notion that we’d be scooping curds all day and listening to Mozart. What a crock!”

As the business grew, the demands of Schad’s goat herd quickly outpaced her cheesemaking, which, though difficult, was far easier to manage than live animals. Schad says goats are “finicky and very fragile,” not at all rugged or eager to eat everything in sight as commonly thought.

“They have multiple births, which is problematic because kids get tangled up and animals die,” she says. “They waste tons of hay because they don’t eat off the ground. They’re so prissy about it. It’s like, ‘Oh, no, that touched the ground where somebody stepped. I can’t eat that!’”

Breeding, to increase herd size, also was complicated, says Schad. Because she needed a year-round supply of milk to balance production flow-through in the plant, she had to keep the herd’s does freshened — bred and pregnant — on a year-round schedule.

Schad says you’ve got to use lights to change the goat’s natural inclinations. “And you’ve got to use a new buck and get everybody all wound up because there’s a new guy in town. There’s goat psychology and there’s goat sex. It’s a science nobody’s really figured out yet. But I really loved the goats. I couldn’t help it.”

Award Winner

A passionate cheesemaker, Schad sought validation for her Chèvres by entering competitions. When one of her cheeses took “Best of the Midwest Market” at a small Chicago show in 1988, she not only caught her peers’ attention, she gained customers. A year later, her goat milk Cheddar took first place at an American Cheese Society (ACS) competition, but 1995’s ACS “Best of Show” award for her Wabash Cannonball truly elevated Capriole as an industry leader and innovator. The 15 awards listed on Capriole’s website is incomplete, she says, but she likely won’t update it.

“Awards are great, and we’ve won a lot, but it’s not what I focus on,” says Schad, who insists on the pronoun “we” when referring to praise of her brand. “You can’t do this alone and have a viable business.”

Even with two decades of cheesemaking experience to her credit, Schad realized on a visit to France’s Loire Valley in the 1990s how far her Chèvres needed to progress to become world-class products. Her palate was changed by those French Chèvres’ rinds, which were sweeter and more delicate than hers. She discovered that Capriole’s Penicillium mold source was the issue, overwhelming her Wabash Cannonball Chèvre. By comparison, the French Geotrichum mold was delicate and nuanced.

Problem was, there was no commercial strain of Geotrichum available in the United States, leaving Schad seeking help to cultivate her own. Her salvation came at the hands of “The Cheese Nun,” properly known as microbiologist Noella Marcellino, a nun from the Order of St. Benedict.

“She’s the cutest thing,” says Schad, “wearing a full habit with a microscope around her neck.”

After she and Marcellino cultivated the mold, Schad transitioned it to the Wabash Cannonball, which “changed its profile like I couldn’t believe! I know it sounds creepy to say it, but I love that mold. When I tasted it in France, I knew what I wanted to do.”

Schad leads me to a table where a cheesemaker is boxing a fresh batch of Wabash Cannonballs, their young, grey-blue rinds still smooth. Later, she offers a picture of a fully aged cannonball, whose wrinkles mirror the convolutions of brain matter.

“Those deeper wrinkles are proof that the mold is changing the inside paste from the outside,” she says. “It’s just magic.”

Her Sofia Chèvre, a three-layered rectangle divided by ash, is another “geo-mold cheese,” she says. With just

a scrim of a rind compared to the Wabash, the paste is exceptionally light and well-suited as a dessert offering.

Longtime Capriole customer Dean Corbett, chef-owner of the nationally regarded Corbett’s: An American Place in Louisville, says Schad’s cheeses are everything chefs want in a local market product.

“It’s right there, 45 minutes from my restaurant. I know the cheesemaker and I know the product is maybe the best there is,” says Corbett. “You get cheeses from Judy, and they’re so good that you let them stand on their own because you want a customer to taste them first by themselves. Add the options, like fig preserves or a good balsamic, after that, but get to know that cheese first.”

Capriole Cheese: Better than Ever

“I am old, and I’ve got too many stories to tell,” Schad says apologetically, working to return to a line of conversation about the details of her business. Multiple times throughout the morning her thoughts return to her wonderful goats. That pattern begs the question of whether she misses them.

“No,” she says, almost before the question is asked. “No, I don’t.” Yet, it’s telling that her nearly constant smile disappears with her answer.

“The day we sold the herd, that was a bad day,” she says. “And I guess the days before that, trying to imagine who I would be without those animals, those were tough, too.”

She admits to crying a lot when “my girls were gone,” but says some of those tears fell because “I was worried nobody would want to buy them. But I still have some.”

In a barn she calls the “old lady goat nursing home,” which houses 15 former milkers, the goats draw near to Schad at the gate before retreating.

“These are goats that are 11 to 14 years old, which is significant when you know that six to seven years of life is good for a goat,” she says. Schad points to a larger barn that once held the whole herd. It’s silent now and she hasn’t entered it since the herd left in December of 2012.

“I won’t go in there. I just can’t do it,” she says. “Maybe I miss them more than I want to admit.”

What she doesn’t miss is the toil required to maintain the herd, the challenge of finding and keeping good farmhands and the distraction from making cheeses — her calling. Sans goats, she’s fully focused on leading and training her four-man staff.

“Without the herd, I have a life,” she says. “Mary Keehn and I went to Jamaica in 2012 for a vacation, and she said, ‘You’ve got a huge liability on your hands. You’ve got to get rid of those animals.’ I knew she was right.” An even better confirmation of Keehn’s advice is customer praise for her cheese.

“Stinky Bklyn called us recently to say they just received an order of our cheese and that it’s just fabulous,” she says. “Cheese shops almost never do that, especially if your product is hit-or-miss, like ours had become sometimes. So when a customer goes out of their way to compliment you, it says a lot. It says we’re doing it right.” CC